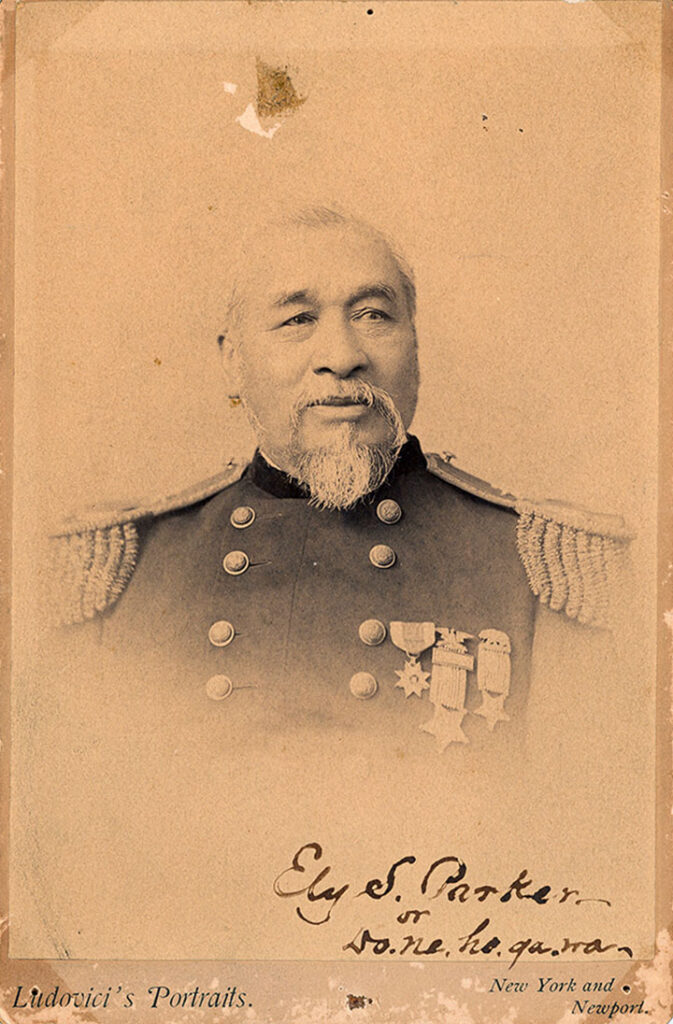

1828-1895

General Ely S. Parker

By the time Do-ne-ho-ga-wa made his home in Fairfield, he had been known as Brigadier General Ely S. Parker for over a decade. Born on the Tonawanda Reservation in Western New York State in 1828, Parker, then called Hasanoanda, was one of the many Seneca children sent to be educated and indoctrinated in a repressive “Indian Boarding School.” Here, he would assume the name “Ely S. Parker” after a minister employed at the school.

Parker excelled in school and was quickly recognized by the Seneca as an outstanding leader. At eighteen years old, he translated for elders and advocated for the preservation of his community’s territorial rights in Washington, D.C. While this first campaign in his career was unsuccessful, it launched Ely Parker into a life of trailblazing firsts for Indigenous people in America.

Early on, Parker faced intransigent racism. After studying law, he was excluded from the New York State Bar, as his Native heritage made him ineligible for US citizenship. He quickly pivoted to engineering. He lent his expertise to the construction of the Erie Canal and successfully fought against land companies trying to take tribal lands. Noticing his acumen for pushing back against a siege of anti-Native federal and state policies, the Seneca elected Parker to sachemdom. His engineering work also caught the attention of General Ulysses S. Grant. The two men became friends and would ascend the ranks of the United States military together.

By the conclusion of the Civil War, Parker had become General Grant’s military secretary, fighting battles by his side, strategizing, and drafting much of Grant’s correspondence. It was Parker who wrote the terms of surrender which Confederate General Robert E. Lee accepted in Appomattox. According to General Parker himself, he had a terse exchange with Lee as he signed.

Do-ne-ho-ga-wa’s career after the Civil War was no less impressive. When General Grant became President Grant in 1869, he appointed his old friend as Commissioner of Indian Affairs, making him the first person of Native heritage to hold the title. In this role he attempted to end the antagonistic stance of the U.S. against Native nations. But Ely Parker’s career as Commissioner was brought to a quick end, after being wrongfully accused of mishandling government money.

His career rapidly spiraled out. He took an administrative job in the New York Police Department but lost much of his money in a sharp economic downturn. It was only at the end of his life that he decided to make a new start in Fairfield, with his much-younger wife Minnie, and infant daughter Maud.

Ely S. Parker would spend the remainder of his life here with his family, relying on the assistance of friends and neighbors. When he died in 1895, Parker was buried in the Oak Lawn Cemetery. But the Seneca wanted the esteemed sachem to return to his tribal nation. His body was disinterred and reburied next to Chief Red Jacket in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo, New York.

Caleb Brewster (1747-1827)

Caleb Brewster knew the Long Island Sound better than almost anyone. Originally from Long Island, Brewster made his living as a whaler, piloting his boats into the Atlantic and bringing whale oil back to New York and Connecticut. As a result, he likely would have been forced to deal with British restrictions on trade and the looming threat of being drafted into the Royal navy. Brewster’s dislike of the monarchy would have only grown when troops occupied his hometown of Setauket in Long Island, turning the Presbyterian church into a fort.

Shortly thereafter, Major Benjamin Tallmadge, George Washington’s top intelligence officer, recruited Brewster and a number of other Long Island residents to secretly funnel sensitive information about British troop movements through occupied territory and back to General Washington. Brewster, being a skilled sailor, was tasked with relaying the messages across the Long Island Sound, darting back and forth from Setauket to his new home along Fairfield’s Black Rock Harbor.

The Culper Spy Ring, as it was called, exposed the truth about General Benedict Arnold’s loyalties, prevented George Washington from being captured by the British, and helped American troops preempt Loyalist tactics. After the Revolution concluded, Brewster, who had sustained serious injuries in his service, settled down in Fairfield with his wife Anna Lewis. They raised a family at their farm, located at what is now Ellsworth Park.

Caleb Brewster died in 1827, and is buried close to the Fairfield Museum in the Old Burying Ground.

1859-1934

Mabel Osgood Wright

Born in 1859, Mabel Osgood Wright was the daughter of Reverend Samuel Osgood, a prominent minister from New York. When she was still a child, Wright moved with her family to Fairfield. Her father built the Mosswood mansion on Unquowa Road and preached sermons from the “Pulpit on the Rock.”

Rev. Osgood entertained esteemed guests from around the country at the estate, introducing his young daughter to a world of possibilities. But when Wright wanted to attend Cornell University’s Medical School, her father’s support for her education faltered. She began writing early on, publishing for the first time at 16 in what would become the New York Post.

From her home in Fairfield, she became enraptured by nature, particularly birds. After marrying James O. Wright, a dealer in art and rare books, she began churning out book after book, documenting plants and wildlife in accessible prose. Her deeply-researched writing quickly won her nationwide recognition and put her in contact with some of the United States’ earliest conservationists.

In 1898, Mabel Osgood Wright founded the Connecticut Audubon Society, which still works to preserve nature and establish bird sanctuaries across the state today. Wright would spend the rest of her life in Fairfield, writing more books, lending her voice to activist causes, and eventually establishing the Birdcraft Museum.

In her leisure time, she was an avid photographer, taking hundreds of photographs of Fairfield, forming a collection now in the care of the Fairfield Museum.

Wright died in 1934 and is buried in Oak Lawn Cemetery.

Prince and Prime (1779)

There is startlingly little information about these two pioneers of human rights from Fairfield. When they were born, when they died, and almost all other aspects of their lives are a complete mystery. This is a typical problem for enslaved people. As a person’s property, little attention would have been paid to their family ties, their desires, or their lived experiences. Of the more than one thousand enslaved Black and Native residents of Fairfield, however, Prince and Prime stand out.

Prince was the enslaved property of a man named Stephen Jennings, whereas Prime was kept as a slave by Samuel Sturges. Like many enslaved people, Prince and Prime strove for freedom above all else. But unlike others who resisted by slowing down forced labor, and fleeing enslavement, Prince and Prime banded together and took their demands to court. On May 11, 1779, the two men created a petition, with Judge Jonathan Sturges serving as a scribe. In a passionate plea for human rights, they stated:

“altho our Skins are different in Colour, from those who we serve, yet Reason & Revelation join to declare, that we are the Creatures of that God who made of one Blood, and Kindred, all the Nations of the Earth; we perceive by our own Reflection, that we are endowed, with the same Faculties, with our Masters, and there is nothing, that leads us to a Belief, or Suspicion, that we are any more obliged to serve them, than they us.”

Their petition was denied outright by the Connecticut General Assembly, and slavery would continue in the state of Connecticut for nearly 70 years. Despite his role in the petition, Judge Jonathan Sturges would own at least eight enslaved people.

The fates of Prince and Prime are entirely unknown.

1897-1967

Margaret Rudkin

Margaret Fogarty Rudkin was born in 1897 to parents of Irish heritage. During her childhood in Manhattan, her father Joseph worked odd jobs, paving streets and selling lumber. Rudkin grew up in this working-class environment, taking a job as a bank stenographer as a teenager. It was probably here that Margaret Fogarty met her future husband Henry Rudkin, a veteran who served in the unsuccessful campaign to capture the Mexican revolutionary and guerilla leader Pancho Villa.

Henry Rudkin worked at the New York Stock Exchange at a time when there were few positions more lucrative. He and Margaret Fogarty married in 1923, propelling Margaret into a life of extravagant wealth. The Rudkins began raising a family in Greenwich Village, but not without the help of at least six servants.

A few years later, the family moved to Fairfield: “the countryside.” They called their new home, a massive estate on Sturges Highway, “Pepperidge Farm,” after an ancient pepperidge tree that grew on the property.

As the family settled into their new life, Margaret Rudkin became concerned with her youngest son’s allergies. She began investigating the issue, consulting with doctors and reading as much as she could about nutrition science. She soon started to experiment with home-baked breads, using as few ingredients as possible. Doctors took notice of Rudkin, seeing her recipes as a potential remedy for children with food sensitivities.

Rudkin’s breads were incredibly popular, and in 1938 she was producing more than 4,000 loaves of bread each week. The demand became too much for her home kitchen and she made the transition from a cottage industry to a baked goods empire, moving production to a facility in Norwalk.

The Pepperidge Farm company, along with Rudkin’s profile grew until she was a nationally recognized force in the American food industry. During the 1950s, she led the company to expand into pastries, other baked goods, and eventually the wildly successful Goldfish cracker.

By 1961, Pepperidge Farm had become a giant. Rudkin seized an opportunity to sell the company to Campbell Soup for tens of millions of dollars, staying on as Campbell’s first female board member. But Margaret Rudkin never strayed from her roots in cooking and experimenting with food. Shortly after the sale, she wrote The Margaret Rudkin Pepperidge Farm Cookbook, which became the first cookbook to make The New York Times Best Sellers List.

Though she died in 1967, Margaret Rudkin’s brand can still be found in grocery stores around the country, now making millions of dollars in sales each year.